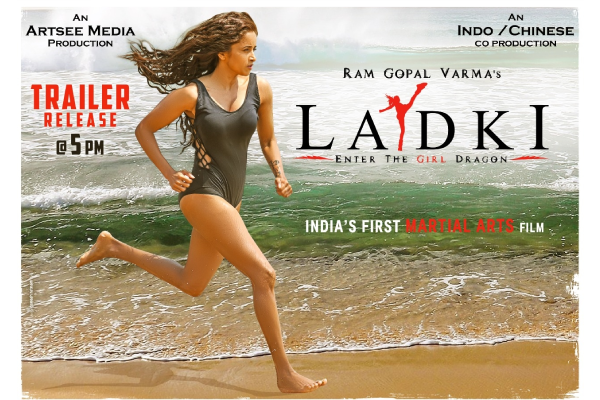

Start the conversation with his cult-classic ‘Shiva’ that was released in 1990, becoming an instant hit in Tamil and Hindi, and filmmaker Ram Gopal Varma smiles, “But it was a blatant rip off of a Bruce Lee film, minus the martial arts of course. All I did was replace the restaurant (in the original) with a college campus. ‘Ladki’ is my tribute to Lee, someone who has fascinated me forever,” he tells IANS.

To be released soon, it is India’s first joint production with China and India’s first release in China after the Galwan Valley clashes between the two countries. The Chinese version of the film has been titled Dragon Girl.

The director, credited to be the master of Mumbai noir, who has to his credit major hits like ‘Satya’, ‘Sarkar’, ‘Company’, ‘Rangeela’ and ‘Raat’ among others says that his fascination for Bruce Lee goes much beyond his martial arts. “There was an underlying philosophy about the man, something that makes him immortal. It is that spirit that I have tried to capture in ‘Ladki’. The protagonist of my film is a woman because no man can come near the man I so idolise.”

Varma who has worked in multiple genres says that it is the dark side of people that has always interested him. “Normal people bore me as does normal situations and families. I have a tendency to take on something that intimidates me no end.”

Varma never went to a film school but immersed himself in foreign cinema as he ran a video library, shocking critics and audiences alike with the very guerrilla way ‘Shiva’ was made, something reinforced with ‘Satya’, post which more than 20 steady-cam rigs were imported by different production houses.

“I remember Boney Kapoor telling me that he could not believe that an outsider like me, who has never lived in Mumbai could make a ‘Satya’. I told him that is precisely the reason why I could. You see, as an outsider, I could see what the people of Mumbai took for granted. I remember being extremely fascinated when I saw the Dharavi slum, the trains, all the subways. Frankly, we had to adopt the guerrilla-style it was not possible to shoot in very crowded localities with a huge set-up. Small crews had to take two-three cameras and dive in. Of course, many cinematographers resist the steady cam saying that it cannot be balanced and the focus cannot be controlled etc. But my point is, why is it important for a chase shot to be perfectly balanced? Why is perfection so important?”

Talk to him about what he thinks of contemporary directors like Anurag Kashyap, Madhur Bhandarkar and Hansal Mehta who worked with him at one point, and he asserts, “To be honest I really don’t follow their work. I generally watch foreign films and documentaries. And this is not meant as disrespect to them. Just that one’s time is limited.”

One of the few directors who made an Indian horror movie (‘Raat’) that actually managed to scare the audiences, during the era when ghost films came across as comic, he feels that it was the subtlety of ‘Raat’ that did the trick. “I do not believe in over-the-top. Also, my references and contexts from the very early days have been Hollywood. So obviously, horror for me would be ‘The Exorcist’ and ‘The Omen’.”

Even as small film schools are mushrooming all over, including in tier-II cities, Varma feels that the very concept of formal education in cinema is outdated. “During my time, we didn’t have access to film tools or the industry to understand the technical side of the craft. Today, in this age of the Internet, you can learn a lot yourself. Someone sitting in a remote corner in Uttar Pradesh can make a film with the quality of what a so-called Bollywood guy would make. The technology is there, it is all about how you tell the story. We needed film schools 40 years back, not now. If you look at history, it’s extremely rare that an institute pass-out has become a director of some significance.”

Adding that the many OTT platforms we have today allow filmmakers to cater to a niche audience, he says, “Also, they prefer a very individualistic style of filmmaking. And being self-taught comes in handy here.”

Does it bother him that media which hailed him as a master after ‘Satya’ has been much unkind to him in the past few years?

“Not at all. I think that this is a cycle, and should be accepted. People like to be negative as that gives them a certain kind of satisfaction. And that holds true for me too. Also, the fact that I seem to be completely radical in my approach, uncaring and not politically right most of the time gives them a great chance to some heat off on me. Anyways, it doesn’t make a difference to me — I am in this world for doing what I am passionate about. It just does not matter whether they praise or criticise me. And yes, I am excited about all my films. I have told that a thousand times, but people want to hear what they want to. I have enjoyed each film of mine – every hit, every failure.”