By Promit Mukherjee and Rafael Nam

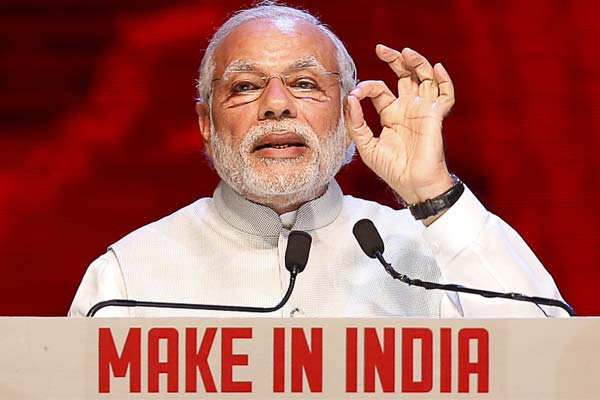

MUMBAI (Reuters) – Thousands of people and mascots of lions swarmed the weekend opening of a “Make in India” drive to attract foreign direct investment, pitched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi as “the biggest brand that India has ever created”.

The week-long event, the boldest since Modi launched the initiative to emulate China’s export miracle back in 2014, seeks to “spark a renewed sense of pride in India’s manufacturing”, its marketing blurb says.

But even as the Make in India hype scales new heights, some bosses question Modi’s delivery on promises to make it easier to do business, while marketing experts caution against creating unrealistic expectations.

“When you over-communicate and you under-deliver, the biggest risk is that you begin to lose trust,” said Chandramouli Nilakantan, CEO of Blue Lotus Communications, a branding and public relations consultancy.

On buzz alone the effort got off to a great start, with the prime ministers of Sweden and Finland attending Saturday’s gala opening hosted by Modi.

On Sunday, delegates thronged the 10 pavilions erected for the event in Mumbai, India’s financial capital. Around 2,500 foreign companies and 8,000 domestic companies were expected to attend, organizers said.

Yet on the ground, the experience of businesses is more prosaic: Twenty months after Modi swept to power with a promise of growth and jobs for India’s 1.3 billion people, executives say more needs to be done, including improving infrastructure.

More pressingly, key legislation such as a goods and services tax and land acquisition bill are stuck in parliament, just as global competitors such as Vietnam step up their own reform efforts.

“Make in India is a great initiative and has created a lot of positive sentiments,” Vikas Agarwal, general manager of mobile phone maker OnePlus in India, told Reuters.

“Now the government needs to follow up with policies. That includes providing custom duty and export incentives, tax rationalization and removal of ambiguous land acquisition policies.”

MAJOR WINS

Make In India has scored major wins, including a pledge by Taiwan’s Foxconn <2354.TW> to invest $5 billion in a new electronics manufacturing facility.

That has helped foreign direct investment to nearly double to $59 billion last year, the seventh most in the world, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Yet in critical aspects, India remains far behind its goals. The proportion of manufacturing to gross domestic product has been stuck at around 17 percent for five years, below the government’s goal to ramp it up to 25 percent, according to the Boston Consulting Group.

India has only created 4 million manufacturing jobs since 2010, according to Boston Consulting. At the current rate, India may only create 8 million jobs by 2022, well below the government’s goal of 100 million.

Professor Ravi Aron, a U.S.-based expert in manufacturing, said India was ill-suited for a Chinese-style export boom, because it lacked the infrastructure and the skills for its exports to compete internationally.

“It should not be called ‘Make in India’ but ‘Make In Spite of India’,” said Aron, of Johns Hopkins University, advising the Indian government to scale back its ambitions and focus on its growing domestic market.

(Editing by Douglas Busvine and Michael Perry)