About 350 people die every day on India’s roads—more than any other country—with those under 18 and two-wheeler riders most vulnerable, according to various data.

An Airbus A320 carries roughly 180 passengers, so the daily death toll on India’s roads is almost double that figure. “If (two) planes full of people crashed every day, wouldn’t the situation get more attention?” said Piyush Tiwari, founder and president of Save LIFE, an advocacy that has used right-to-information queries to disaggregate traffic-death data.

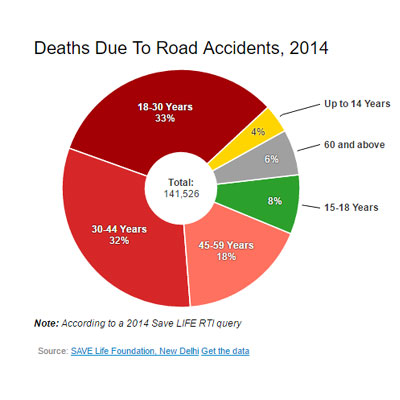

Indians under 18 years constitute 11.93% of traffic fatalities, according to a 2014 Save LIFE RTI query. The toll primarily stems from rash driving, below-global-standards roads and a shunning of safety—either deliberately or through ignorance.

Source: Save LIFE Foundation

It was in February that Union Road Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari told Parliament that 130,000 people die in 500,000 mishaps on Indian roads.

In 2015, a World Health Organization (WHO) study said India did not meet international standards of road safety, the areas of vulnerability being over-speeding, not using helmets, not using or misusing seat-belts (mandatory for the last 28 years) and the lack of child restraints.

The study rated India’s enforcements in these critical areas as 4/10.

“Even those who strap themselves in when seated in front often are not concerned when seat belts are not used by passengers at the back,” said Tiwari. “They overlook the fact that in case of an accident, people in the back seat are often deadly projectiles, hitting the windshield and harming those strapped in front too.”

IndiaSpend has reported India’s tide of road accidents here and here.

Children suffer most in accidents, holding baby in arms is unsafe

The year-old baby was cradled in its mother’s arms, as most babies travelling in Indian cars are. When the driver slammed on the brakes, the child flew out of the window and died instantly.

Mohammed Imran narrated the death of a relative’s child to illustrate the widespread ignorance across India about using a car seat for children.

“While it’s true that a car seat is expensive, (a basic model can cost Rs 4,000, most are imported), I always feel that money is not the issue here,” said Mohammed Imran, founder of the Safe Road Foundation, an advocacy. “When you can afford a car, why not a car seat?”

Car seats, he said, are not enough. You must know how to use one. For instance, infants should use rear-facing infant seats, toddlers front-facing seats and older children booster seats.

“One must first challenge the attitude that a child is safer in his mother’s arms and make car seats readily available across the country instead of selling these only in select stores,” Imran said.

Two-wheeler riders most accident-prone, as tide of vehicles grows

Two-wheeler riders are clearly most vulnerable, according to 2013 WHO data. As many as 34% of two-wheeler users who died in accidents—nearly three times the number who died in car accidents—did not wear a helmet.

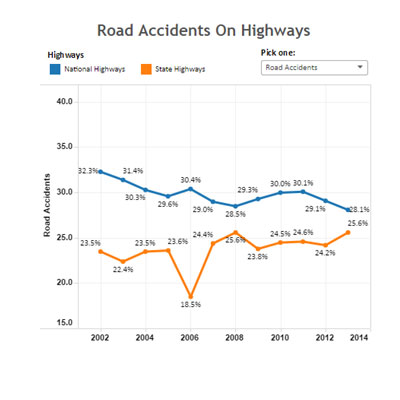

Source: Transport Research Wing

India’s rising, chaotic traffic makes them even more vulnerable. India had 15 million cars in 2014, or 13 per 1,000 people, according to this 2014 report from The Energy and Resource Institute. Overall, that is not a lot—Brazil had 249 cars per 1,000 people, Thailand 206, China 83 and the US 797, according to these data.

But the density of cars is higher in burgeoning metropolitan cities: Delhi had 157 cars per 1,000 people, Mumbai 35, Bangalore 85 and Chennai 127.

The rise of distracted driving makes things worse

Apart from traffic density, distracted driving is becoming commonplace, despite the four-fold increase in crash risk when you drive while speaking on a mobile phone, Tiwari said.

Distractions and over-speeding without police checks explains why India is rated 3/10 on enforcement, according to the 2015 WHO report. Controlling and setting speed limits requires a nationwide upgrade, now that roads are better and vehicles faster.

“Many of the current speed limits are based on road parameters that existed in the 1960s and 1970s,” said Tiwari. “So, even if you do stick to the speed limits, often, these are impractical and unviable.”

Battling addiction, a new challenge on highways

Harman Singh Sidhu has been battling the state governments of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan–and liquor vendors in these states—for three years in courts to prevent liquor sales on India’s national highways.

“There is no specific law that prevents liquor vendors from selling along India’s highways,” said Sidhu, president, ArriveSAFE, an NGO based in Chandigarh. “And this is despite evidence that 40% of India’s accidents occur from drink driving.”

There were as many as 185 unauthorised liquor shops along a 291-km stretch of the Panipat-Jalandhar National Highway linking Haryana and Punjab, according to an RTI response filed by ArriveSAFE in 2012.

Drivers along these highways battle other addictions too. In an effort to stay awake, many consume a stimulant called poppy husk, an issue that requires greater awareness and advocacy and which Arrive SAFE is engaged in addressing.