Courtesy Indiaspend

As new education minister Prakash Javadekar takes charge of a ministry that appeared to impede the Prime Minister’s desire to see world-class Indian universities, step one could be to get his ministry’s first-ever national ranking in order.

The Ministry of Human Resource Development’s maiden ranking exercise for Indian universities, India Rankings 2016—a guide for students—lacks three key criteria used in prestigious university ranking exercises globally, such as Times Higher Education World University Rankings, a list of the world’s best universities, compiled since 2004.

The Indian ranking criteria, listed in the National Institutional Ranking Framework, lacks information on doctorates awarded, institutional income and global reputation of Indian universities, which, in general, fall short on faculty-student, male-female and international-local student ratios, according to an IndiaSpend analysis.

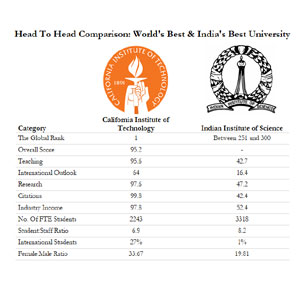

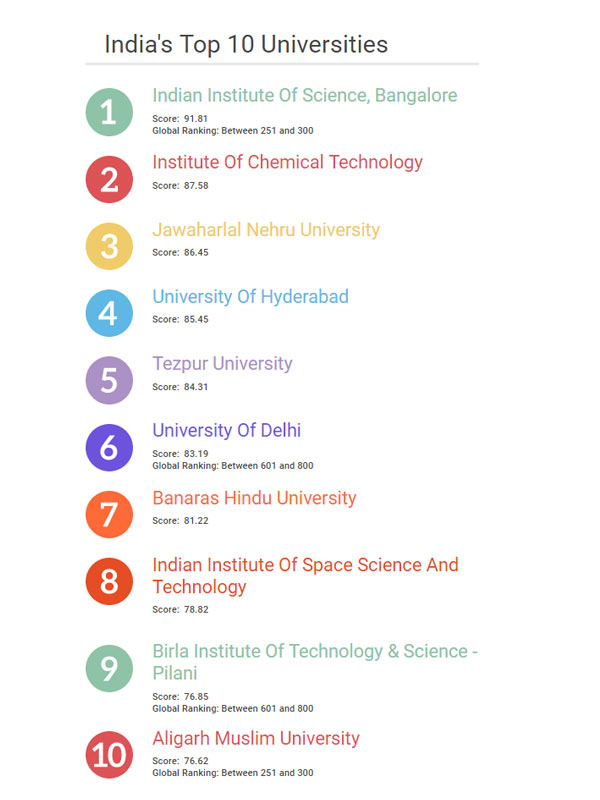

The world’s best university, according to The Times’ rankings, is the California Institute of Technology, or Caltech. India’s best, the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, is ranked between 251 and 300—universities are banded after the first 200 ranks—the only Indian higher-education institution in the top 300. China is the only BRICS economy with three universities in the Times’ top 100 universities list: Peking University, ranked 42, University of Hong Kong, ranked 44, and Tsinghua University, ranked 47.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants 10 public and private institutions to be world-class teaching and research institutions over the next five years, “to allow ordinary Indians access to affordable world-class degree courses”, but that is inadequate for a country where 33.3 million students were enrolled in 716 universities and 38,056 colleges, according to the 2014-15 All India Survey on Higher Education.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants 10 public and private institutions to be world-class teaching and research institutions over the next five years, “to allow ordinary Indians access to affordable world-class degree courses”, but that is inadequate for a country where 33.3 million students were enrolled in 716 universities and 38,056 colleges, according to the 2014-15 All India Survey on Higher Education.

What’s missing in India Rankings 2016

Doctorates awarded: India Rankings ignored the number of doctorates awarded, important criteria—the doctorate-to-bachelor’s ratio and the doctorates awarded-to-academic staff ratio—to indicate “how committed an institution is to nurturing the next generation of academics” and “the provision of teaching at the highest level that is thus attractive to graduates and effective at developing them”, according to the Times Higher Education criteria.

“The quality and quantity of doctorates in the country is very important for India, doctorates drive the quality and level of research happening, which in turn, boosts innovation and economic growth,” said Furqan Qamar, secretary general, Association of Indian Universities.

India had 20,425 and 22,849 enrolments in master’s and doctoral programmes, respectively, in 2013, making up 0.67% of all higher-education enrolments, when it should ideally be 5%, according to Qamar. Too few of these enrolments were in engineering/technology (5.9%), medicine/health sciences (2%) and agricultural sciences/technology (2%), “disciplines that are typically associated with applied research and which therefore, go on to further technological advancement”, said Qamar. Most were in pure sciences (32%) and arts/social sciences/humanities (35%).

Income: Income of any kind is absent from the India Rankings framework for universities. Times Higher Education considers institutional income, to provide “a broad sense of the infrastructure and facilities available to students and staff”; research income, “crucial to the development of world-class research”; and industry income to capture “the extent to which businesses are willing to pay for research and a university’s ability to attract funding in the commercial marketplace”.

India Rankings evaluates learning resources by assessing the actual facilities, a surer measure in a country where colleges can exist only on paper. However, institutional income can additionally indicate available resources for faculty remuneration, which, in turn, determines quality of faculty and research.

Assessing research income would show the “harsh reality” of research grants in India, said Rajan Saxena, vice chancellor, Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, Mumbai. “Globally, governments are the biggest grant-makers for research, but in India, the government tends to discriminate between institutes of national importance and the private sector,” said Saxena. “Research grants should be given wherever potential and talent exist.”

Likewise, assessing industry income would show the disparity between Indian academic research aims and industry needs.

“Most ongoing research in Indian universities is theoretical and incremental in nature whereas industry seeks research outcomes based on looking at issues in a fundamentally different way,” said Saxena.

“In developed nations, industry looks to universities for new ideas for potential use in the future. Indian industry is more demanding; it looks for problem-specific research that ends in almost a prototype of the device or process, so that product development can quickly ensue,” said Bishnu P Pal, a professor at the School of Natural Sciences, Mahindra Ecole Centrale, the Mahindra group’s engineering college in Hyderabad.

Most research in Indian universities is by doctoral students for their thesis, said Pal.

Global reputation: A global reputation survey result makes up 50% of the Times survey’s teaching score and 60% of the research score. To evaluate institutional reputation, India Rankings engages with all sorts of stakeholders in India. This is not enough, said experts. Indian universities must get known for excellence overseas.

Weak spots measured in India Rankings 2016

Three criteria figure in both India Rankings 2016 and the Times’ rankings, but these are also areas where Indian higher-education comes up short.

Faculty-student ratio: India’s leading university, IISc, has a staff-to-student ratio comparable with the world’s best, 1:8.2 versus Caltech’s 1:6.9. However, Indian institutions lower down the order fared poorly. For instance, Delhi University, ranked sixth in India and in Times’ 601-to-800 rank band, had a faculty student ratio of 1:22.9.

“India’s average student-faculty ratio for a higher educational institutions have been hovering at about 27,based on sanctioned faculty positions,” said Qamar. “On the basis of the occupied faculty positions, the ratio would nearly double.”To attract quality faculty and boost the ratio to an average of 10 in universities, India needs to invest more in higher education,” he said

Global students: International outlook is the Times’ composite measure of international-to-domestic-student ratio, international-to-domestic-staff ratio and international collaboration (for research publications). Caltech scored 64 in this category, IISc 16.2. Caltech has 27% international students, against IISc’s 1%.

“A large international footprint both in terms of students and faculty is important for a university because this brings in new ideas and different work culture from all over the world,” said Rajiv Dusane, dean, International Relations, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay. “To facilitate this, we are engaging with the ICCR (Indian Council of Cultural Relations) and Indian embassies. We are trying to bring in more international faculty by way of visiting and adjunct faculty schemes.”

Female-to-male student ratio: Caltech had 33% female students versus 19% in IISc. Although the enrolment of women in higher education rose from 38.6% to 46% between 2007 to 2014, according to the respective All India Surveys On Higher Education, fewer women sign up for engineering and technology courses, 29% at the undergraduate level and 37% at the postgraduate level.

“A higher female-to-male student ratio in academic institutions like IITs is important because there is a need of highly-qualified female engineers in various sectors of technology and education,” said Dusane. IIT Bombay is seeing more women enrol for master’s and doctoral programmes, a trend also visible at the undergraduate level.