The demonetisation of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes will hurt agriculture, informal sector workers—about 482 million people who earn cash incomes—and disrupt India’s consumption patterns for at least the next quarter, according to an assessment released last week by Deloitte, an international consulting firm.

In contrast, sectors like e-commerce and payment banks, payment gateways are set to gain as transactions using cashless methods will increase over the coming months, the Deloitte report said, emphasising that “the long-term outlook remains positive”.

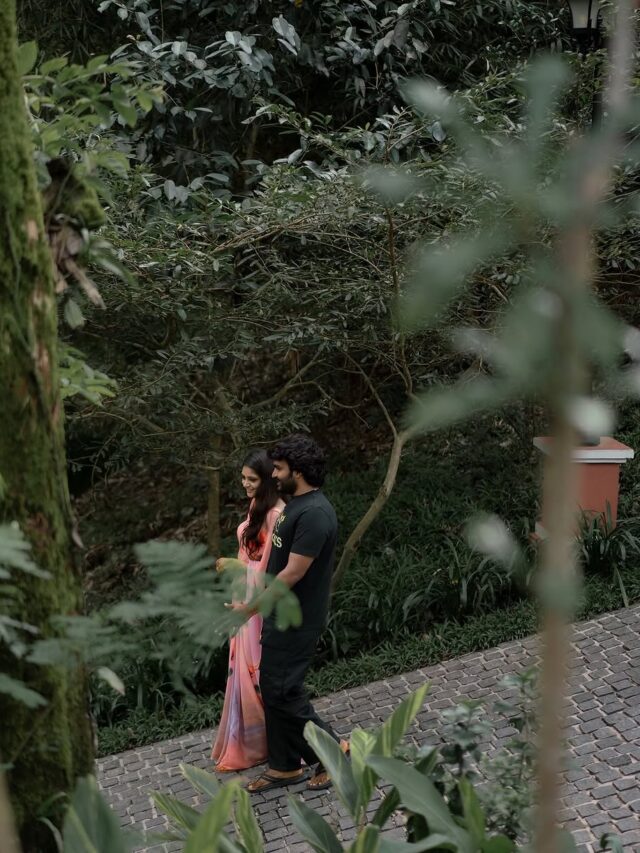

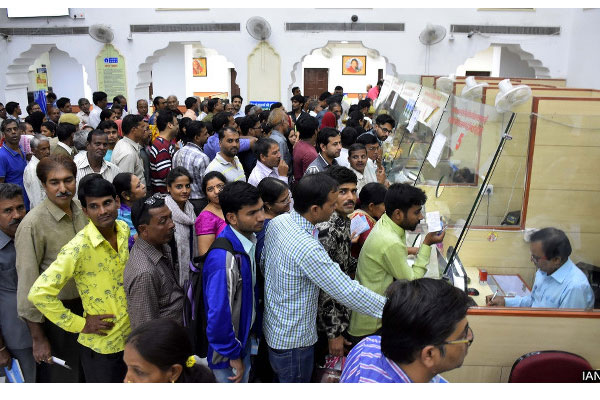

The lines to exchange defunct Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes grew across India, as fraying tempers and scuffles were reported.

The Prime Minister–who had promised working ATMs by day three–pleaded for 50 days to set the chaos right, and his government extended the validity of the old notes in select transactions for another 10 days.

While the short term impacts will be pronounced on the brick-and-mortar retail sector like kirana shops, vegetable and fruit vendors, long-term negative impacts on the real-estate sector are possible, the Deloitte report said.

“Overall, a likely negative impact on disposable income is expected along with disruption in the consumption patterns of the general populace,” said the report, which called demonetisation “arguably one of the most significant reform measures in its tenure” and “an expeditious move to boldly counter the black money and parallel economy”.

Others are not as optimistic. Demonetisation has perhaps “penalised” the entire informal sector and damaged it permanently”, especially the informal financial sector, which could account for a fourth of bank lending, or 26% of GDP, wrote Pronab Sen, country director of the India Central Programme of the International Growth Centre, a think tank.

“There is no doubt whatsoever that Mr. Modi has pulled off a major political and publicity coup and substantially enhanced his reputation as a muscular leader, but surely somebody needs to ask: at what price?” wrote Sen on November 14, 2016 in Ideas for India, an economics and policy portal.

Rs 14 lakh crore–or $217 billion, 86% of the value of Indian currency then in circulation–became useless from midnight of November 8, 2016, part of the government’s crackdown on black, or unaccounted, money, which accounts for about a fifth of the economy, as IndiaSpend reported on November 8, 2016.

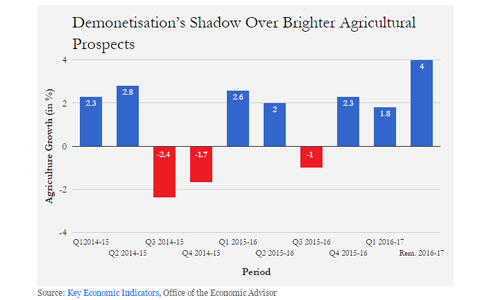

Agriculture, under stress for two years, was forecast to grow 4%

Agricultural growth in India contracted 0.2% in 2014-15 and grew no more than 1.2% in 2015-16, largely because of back-to-back droughts.

Agriculture was expected to grow at 4% this year according to this October 2016 CRISIL report, but demonetisation is likely to dent that forecast. India is currently in the midst of the winter sowing season, but farmers are reported to be running out of cash to buy seeds

ndian farmers expect a record harvest this year, as IndiaSpend reported in October 2016, but the rural economy–on which 800 million people, or 65% of India’s population, depend–is largely driven by cash. Farmers buy seeds, fertilisers and farm equipment in cash, pay their workers in cash, and traders and commission agents pay farmers in cash.

The shortage of cash is spreading anger in the countryside.

Informal economy has limited access to Internet, online payment

The informal economy—which presently employs more than 80% of India’s workforce—includes workers in small and medium industries, grocers, barbers, maids and others.

Roadside vendors, cab drivers, kirana stores and medical stores have stopped accepting Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes.

People who do not use debit or credit cards, access the internet or use mobile banking and e-wallets will be the worst hit, said the Deloitte report. India has about 700 million debit and 25 million credit cards, according to this Reserve Bank of India data; about 950 million people (78% of the population), do not have an internet connection.

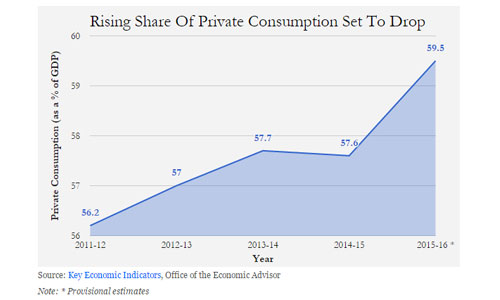

The demonetisation-led slowdown may also impact a key economic driver, private consumption, the things that people buy.

Private consumption, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) has been steadily rising over five years to 2015-16, according to data from the office of government’s economic advisor.

E-commerce, payment companies to benefit

As e-commerce websites stop cash-on-delivery–the most favoured option for Indian online shoppers, comprising 80% of sales–and struggle to hand over to banks the money they collected after demonetisation, the report predicted a rebound that will benefit both the e-commerce industry and companies facilitating payments to it, such as payment gateway companies, payments banks and electronic money transfer portals.

Online transactions in India rose 40% in 2015, IndiaSpend reported on November 12, 2016.

Other possible impacts that the Deloitte report listed: a hit on foreign trade as the rupee currency appreciates; lower inflation and cheaper prices, especially in the real-estate sector.

Purchasing power of Indians in peril, says report

“As far as the real economy is concerned, there is going to be huge blow to purchasing power. All kinds of people who were accepting notes are going to refuse to accept the notes,” economics writer Swaminathan Anklesaria Aiyar, told the Economic Times.

“Domestically, there could be some turmoil as the effect will be disproportionately felt by the lower and upper income classes,” the Deloitte report said.

Courtesy IndiaSpend