[intro]In his new book, Jairam Ramesh who worked extensively with PV Narasimha Rao compares the style of the then Prime Minister with obvious digs at PM Narendra Modi. A timely recap of Rao with a lesson or two for India’s current Prime Minister.[/intro]

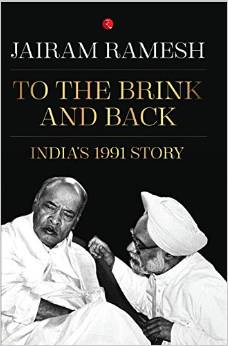

You don’t usually expect a Congressman to pay left-handed compliments to PV Narasimha Rao, one of India’s most-revered Prime Ministers but someone who was disowned by his own party members, thanks to unbridled sycophants of Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi. It is therefore, surprising that Jairam Ramesh, former UPA Minister for Environment writes a book on PV Narasimha Rao’s dramatic handling of India’s greatest economic crisis of 1991. The book is entitled: To The Brink and Back: India’s 1991 Story and covers those crucial 100 days of the Rao government taking charge and coming to terms with a bankrupt economy shackled in license Raj and a market that doesn’t favor all the factors that build the economy – land, labor and capital. But the book tempts you to draw a parallel to Modi’s style of functioning versus Rao’s.

Succinctly written by Jairam Ramesh, the book giving a ringside view of all that happened between Narasimha Rao and Dr Manmohan Singh and the key think-tank who took those courageous economic decisions – which included a two-stage devaluation of the rupee, four gold transfers, and an Industrial Policy that would have been unthinkable even by today’s terms. More importantly, the three measures of LPG cylinder – Liberalisation, Privatization and Globalization that formed the bulwark of today’s economic foundations – all were masterminded by the Rao Regime. The Book gives the dope on the drama behind each of the decisions taken amidst stiff opposition from both within the Congress Party and the allies in the Left and National Front who bulldozed the government. It was the era when the Left was still powerful and leaders like Jyoti Basu were unconquerable and the media was giving bad press on reforms unleashed – given the turmoil that followed the Berlin Wall collapse and the unravelling of the Soviet Union republics.

Succinctly written by Jairam Ramesh, the book giving a ringside view of all that happened between Narasimha Rao and Dr Manmohan Singh and the key think-tank who took those courageous economic decisions – which included a two-stage devaluation of the rupee, four gold transfers, and an Industrial Policy that would have been unthinkable even by today’s terms. More importantly, the three measures of LPG cylinder – Liberalisation, Privatization and Globalization that formed the bulwark of today’s economic foundations – all were masterminded by the Rao Regime. The Book gives the dope on the drama behind each of the decisions taken amidst stiff opposition from both within the Congress Party and the allies in the Left and National Front who bulldozed the government. It was the era when the Left was still powerful and leaders like Jyoti Basu were unconquerable and the media was giving bad press on reforms unleashed – given the turmoil that followed the Berlin Wall collapse and the unravelling of the Soviet Union republics.

The country was on the brink of an unprecedented Balance-Of-Payments Crisis and nobody was prepared to take the tough decisions that needed to be taken as the economy came to a grinding halt; we had two weeks of oil supply based on our gold reserves. And Rao even ordered a chartered plane to Brunei to seek an Emergency Loan in US Dollars from the Sultan – something that Dr Manmohan Singh, the then Finance Minister didn’t endorse. Inflation touched almost 16.7 per cent by August 1991. It was then that India’s most vulnerable minority government (which even had a No-Confidence Motion passed in the aftermath of these measures) took the steps that included “structural adjustments with a human face”.

In 216 pages, Jairam Ramesh makes many overt and subtle references to Rao’s style of functioning but the timing of the book and his recent interviews holds a mirror to Narendra Modi’s style of functioning too. While we are far better off now than in 1991- We now have around ten month’s reserves to fund imports, our forex reserves are many times more comfortably placed at $ 350 Billion, and our Current Account Deficit is diminishing to finish the year at 0.9 per cent as opposed to the historical average of 3.5 per cent and so on. Clearly, what he says about Rao must be remembered in the context of what Narendra Modi is doing with respect to his potential and performance so far.

In Rao’s first 100 days as PM, India saw two devaluations, a comprehensive recast of India’s trade and industrial policy, a budget that clearly capped the government expenditure and a radical push at labor reforms. His government is itself in minority precariously perched to fall any time (there was no majority in Lok Sabha and an uneven situation in Rajya Sabha prevailed then too without a clear majority to pass the bills). The world also did not think India was any better than countries on the brink of chaos like Pakistan or Iraq or Somalia – Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), infact, was a term first coined in the aftermath of the drastic measures announced by the then Finance Minister in order to attract investments into Indian industry and increase our exports.

By contrast, PM Modi enjoys a grand majority in the Lok Sabha, enjoyed the greatest fanfare on his election both with locals and the diaspora, still doesn’t have a recognized leader of opposition, virtually has no threat from anybody in the ranks who can question him or his decisions but after almost 15 months in rule, his government is running out of steam – both in terms of showing the resolve to push ahead the next-gen reforms but also showing a path of quick resolution of all the stalled projects and litigious issues in the country – there are newly formed states that needed war-room attention, there is a nascent currency crisis given the rapid devaluation of the Chinese Yuan, atleast two major reforms which could energise the land and labor markets – Land Reforms Bill and the Labor Policy Reforms are yet to be passed, and the cost of capital is still high. Despite having the Lower House majority, Modi government has not shown the resilience and the steely determination shown by a minority Rao Government in clearing the hurdles to passage of key bills like GST bill etc and in building a consensus approach. All that the Modi government is interested is in more and more control of the Rajya Sabha seats and take full charge of both the Houses of Parliament.

When Narasimha Rao was the Prime Minister, he knew his time was very limited and options few, but he acted fast what he thought was right for the country unmindful of the repurcussions for the Party; the Congrress survived the full term but never wavered from taking the opposition into their stride. Modi Government has absolute majority but is frittering away precious political capital in the pursuit of policies that are not gaining headline attention anymore. Evidence of proof of FII’s waning interest in Modi is the sharp fall in India’s stock markets and decline of currency. It means the FIIs want to take some money off the table – the money they bet when Modi was elected because nothing significant is happening, of late.

Another point that Jairam Ramesh makes is that Indians are prone to too much eulogisation of politicians – what Ambedkar calls as Bhakti Yoga. He said that the Chinese, by contrast are more objective. Even the great Mao was said to be 30 per cent bad and 70 per cent good. So, he criticizes Rao in his crucial bungling of the issues at Jammu & Kashmir and in Ayodhya while the Bhakts of Modi are never tiring of his foreign junkets and speeches. Jairam Ramesh in his assessment of Rao makes a dig at Modi: “He (Rao) could certainly not be accused of Narendra Modi’s style of arrogance; rather, in him, one could see a strong sense of awareness. His was not the in-your-face conceit of his current successor but the self-pride of an intellectually superior person – of one who knows that he knows.” If only Modi had found a middle-path like Narasimha Rao, to strike a deal or two with Congress in their demands to have a debate on Lalit Modi controversy etc, the Parliament would have seen a fruitful Monsoon session and passage of a few momentous bills.

In summary, Jairam Ramesh’s book is a timely eye-opener for all those who continue to air-lift PM Modi into stratospheres of halo. Let it be known that with no wind beneath his wings during his time, PV Narasimha Rao faced more challenges and yet acted decisively setting history in motion for India. He took most of his opposing tribes into confidence and built consensus one day at a time. By contrast, PM Modi is showing signs of self-congratulatory arrogance and still seeking greener pastures after getting a massive mandate on a platter. In seeking out more and more supporters like new allies in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, he is forgetting that there are allies in Andhra Pradesh and elsewhere who voted for him or supported his party. If he wastes more time in garnering those fragments of power that will give him complete control of both the Houses of Parliament, it will be evening time in 2018 and by then, the stage is set for the next Lok Sabha elections. Hope, PM Modi takes a leaf out of the history books and learns what Narasimha Rao did in his tenure. It is a lesson or two to act in hurry and work with a self-effacing humility. Time is running out for Mr Modi.