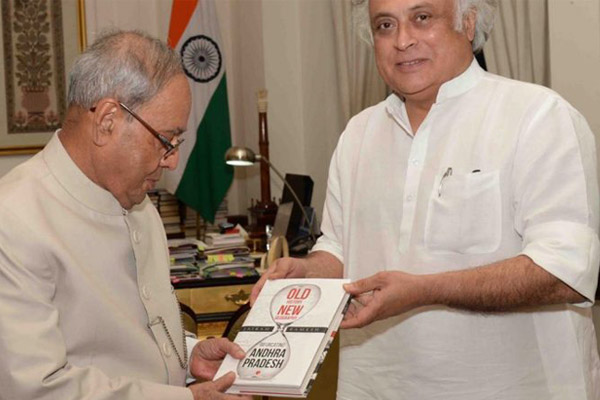

No scoops in this informative read on AP division!

Jairam Ramesh’s book is an engaging account on the process of bifurcation, but barely touches the behind the scenes politics.

By Ramesh Kandula

If you want to know why and how the united Andhra Pradesh was bifurcated, Jairam Ramesh’s book, “Old History, New Geography” will only half-satisfy you. For, as he himself admits, he was not privy to the politics that went into the decision. But that does not prevent him from giving his own clues for the announcement, even while he provides a detailed account of what went behind the actual process of bifurcation, having been the man behind the GoM (Group of Ministers) that was tasked with carrying out the unpleasant business.

It would be surprising to know that a party like Congress with such chequered history and a long association with Andhra politics going back nearly a century would actually rely on the shallow understanding of a politician without a mass base like Ghulam Nabi Azad to finalize a momentous decision like division of Andhra Pradesh. According to Jairam Ramesh, Azad ‘the most ardent advocate of bifurcation’ ‘was able to convince the Congress leadership that bifurcation would yield electoral dividends for the Congress’.

Click here to read about Telugu360 exclusive interview with the author Jairam Ramesh

Jairam’s guess is also that ‘the Congress expected the TRS to merge with it before the 2014 Lok Sabha polls’.

In other words, Jairam was frank enough to admit that the Congress did all this to ‘minimize its losses by protecting itself in Telangana at least’. Not exactly a scoop!

A few other interesting ‘revelations’ in the book include:

When Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, in a long cabinet meeting, asked every member for views, all barring M M Pallam Raju and Kavuri Sambasiva Rao supported the bifurcation. If you remember, the other ministers in the cabinet include Kishore Chandra Deo (cabinet rank), Chiranjeevi (MoS Independent Charge), and Purandeswari (MoS). Not clear whether the latter two attended the cabinet meeting.

The present APCC president N Raghuveera Reddy strongly advocated Rayala Telangana before the GoM, offering to join his native Anantapur district, along with Kotla Surya Prakash Reddy’s Kurnool district, to carve out greater Telangana. Both of them were so enthusiastic about the idea that they in fact drummed up resolutions from around 1,600 gram panchayats from districts favoring merger with Telangana. That such a man was picked up by the Congress to lead their party in Andhra Pradesh post-bifurcation shows the pathetic state of affairs in that party.

Rayala Telangana did indeed get some attention in Delhi, according to Jairam Ramesh, as two bills were prepared – one with a ten-district Telangana and another with a twelve-district Telangana. The proposal, however, failed to muster enough support, as the ‘idea came too late in the day’.

The union territory status to Hyderabad that was bandied about for quite some time in the media by the likes of Chiranjeevi was never seriously considered due to the obvious issue of geographical position of the city.

A more important and substantive proposal mooted by Jairam Ramesh was distribution of revenues from Hyderabad between the two new states for a period of ten years. This would indeed have benefited the ‘residual’ Andhra Pradesh immensely, had it been pushed for by the noisy Andhra leaders who betrayed lack of focus. That is because the HMDA area generated close to half of the undivided state’s own revenues. Jairam apparently favored an independent committee to suggest this distribution. But Chidambaram, who by this time became the Finance Minister, dismissed it as constitutionally unviable.

Another idea that was shot down was that of a common capital governance council.

The Section 8 that came in its place (and which became a bone of contention between the two new states subsequently) was actually dictated by Chidambaram. It is a different matter that not only Section 8 but also the three-page office memorandum issued by the BJP government later was consigned to the dust bin by the Telangana government (thankfully, it doesn’t look like they are needed any more given the change in political realities on the ground). It is to the credit of Jairam that he thought up of such an arrangement to ensure a sense of security prevailed in the common capital, vitiated during the time by vitriolic statements.

Polavaram was essentially a gift to Andhra in lieu of Hyderabad. It was ‘something extra’ for losing out on Hyderabad. Jairam took personal interest in urging Rajnath Singh, the new Home Minister, to issue the ordinance for transfer of seven mandals in Bhadrachalam division right away, as KCR government, once formed, would make it impossible.

While the special category status drama that played out in Rajya Sabha is well-known with Venkaiah Naidu capturing everyone’s mindshare, ironically the very concept of ‘special category status’ got abolished after Modi government came to power.

Curiously, Jairam fails to touch upon the issue of division of assets and liabilities between the two states in detail, which has now become intractable, especially with regard to institutions mentioned in IX and X schedules.

For all their limitations, the Andhra Congress politicians seemed to have understood their fate was sealed once the bill was passed. They told Jairam Ramesh that he had written their ‘political obituaries’!

Telangana is a reality, and so it is easy to be dispassionate now. Jairam talks about a few of the parables that Telangana protagonists were fond of narrating time and again. One is that Jawaharlal Nehru was for Telangana divorce any time, and another is an alleged description of Telangana as masoom bachchi and Andhra as natkhat. Many of us in the past said that there was no recorded evidence of such an analogy. Ramesh too searched in vain for some proof of the utterance but in vain. Likewise, another unverifiable argument was that Indira Gandhi too was supposed to be in favor of AP division earlier, but could not move ahead as the issue was pending with United Nations following Nizam’s petition in 1948. Likewise, I am glad that I was not the only one who felt that the expression ‘residuary’ for the dispossessed state of Andhra Pradesh was belittling. Jairam Ramesh felt the same, and his intervention ensured that ‘successor’ state was used in its place in all official communications subsequently.

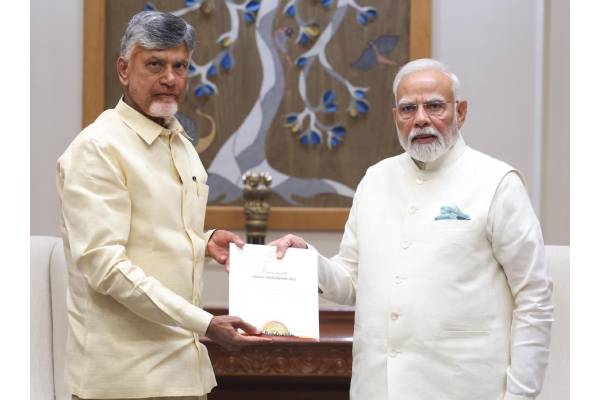

While these old stories may not interest people anymore after the bifurcation, what is evident from Jairam’s narrative is that he did see that AP would be the loser in the bargain, though he himself was sympathetic towards its future and tried to make some amends to the situation. Jairam’s liking for Chandrababu Naidu is well-known – as he says in the book – for putting ‘Hyderabad on the IT map of India and the world…”. He reveals that he was offered an advisory position in the Naidu’s earlier government.

For the record, the book does not have any factual errors with regard to Andhra and Telangana history, or spelling mistakes with regard to names of Telugu politicians, as is wont in non-Telugu writings. But Jairam got one fact wrong. Nandyal, from where PV Narasimha Rao contested for Lok Sabha, is not in Telangana, but in Kurnool district of Rayalaseema.

While the creation of Telangana was an historical inevitability, what many could not fathom is the inept manner in which it was handled despite the fact that the bells of separation were ringing for far too long. However, the bureaucrat-turned-politician, understandably, fights shy of going into this tricky matter in an otherwise informative handbook.

(Ramesh Kandula is a senior journalist and is currently working as Chief Editor of Andhra Pradesh Magazine, Dept of information & Public relations, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh)