Demonetisation’s short-term costs were high, long-term benefit doubtful

When Raghuram Rajan, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), cautioned the government against demonetisation, saying short-term economic costs would outweigh long-term benefits, he was not trying to be prophetic. But a year after Prime Minister Narendra Modi made that fateful announcement in a nationwide broadcast on the evening of November 8, it would seem Rajan’s words had actually become so.

As economists and analysts, corporate honchos and statisticians struggle to gauge the beneficial impact of demonetisation, many of the objectives claimed by the government have fallen by the wayside. New claims and afterthoughts on the note ban by senior politicians in power have remained unconvincing. Demonetisation has raised more questions than it has answered.

The Prime Minister, in banning 1,000 and 500-rupee notes — or 86 per cent of total currency in circulation — had indicated that the decision would help remove black money from the system, rein in terrorism and take fake currency out of circulation. Have these objectives been met?

“Demonetisation was an utter failure. Theoretically it was known it cannot be successful. It could not remove black money, but in turn it has damaged the white economy and growth,” Arun Kumar, former professor of economics at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) told IANS.

The benefits of the decision are yet to percolate to the economy, but the disruption as well as pain that it caused to hundreds of millions was very real, whose lingering effects are seen to this day and, which, at that time, had shaken the country to its core, touching nearly every citizen and visitor.

The overnight serpentine queues for weeks in front of banks, the loss of over a hundred lives in the effort to withdraw one’s own money or change it, and the desperate desire to ensure that cash in hand did not turn to ash took its toll across the country. Was it worth it?

“The government made the elementary mistake of believing that black money is kept in cash. Black wealth can be transacted by non-cash means as well,” said Kumar, who is now Chair-Professor with the Institute of Social Sciences. “Only three per cent of Indians generate substantial black money. But for this, the other 97 per cent had to face the consequences of demonetisation.”

After months of vacillating, and being less than honest with citizens, RBI data in August 2017 said that 99 per cent of the banned currency in high denomination notes had returned to the banking system — Rs 15.28 lakh crore out of the Rs 15.44 lakh crore in circulation on November 8, 2016. The calculation does not take into account the money changed by people in Nepal, where it’s legal tender, or old notes held by many non-resident Indians who could not exchange it within the deadline.

“Indian demonetisation was remarkable, because unlike many countries that faced major economic and political problems after even less drastic measures, this passed off peacefully as most Indians accepted the (wrong) argument that this would end corruption,” Jayati Ghosh, Economics Professor at JNU, told IANS.

“The initial reasons the government had advanced for this move, of reducing terrorism and eliminating both black money and corruption, were rapidly abandoned for other supposed goals, which are also yet to be met. There was no planning before unleashing such a big decision,” she added.

The difficulty in making a cost-benefit analysis is that the move was not purely economic, given the fact that the currency issuer — the RBI — had no role in the decision, as testified by Rajan.

Demonetisation comes across more as a measure of political economy which may appear, on the face of it, to have paid immediate political dividend to the Prime Minister and his party in the Uttar Pradesh elections this year. But the medium-to long-term picture would take a while to clear up, though short-term impact has already taken its toll on growth.

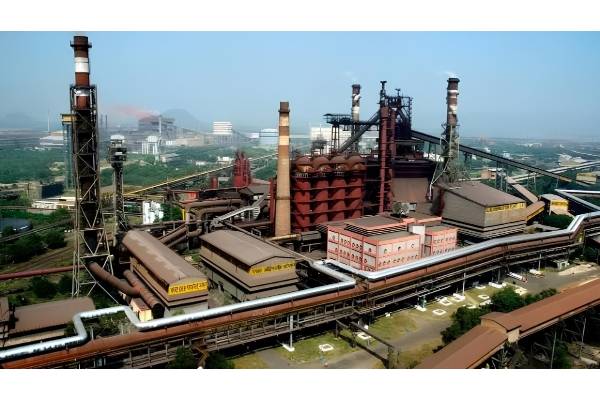

At the end of May, the Central Statistics Office announced that the GDP during the fourth quarter ending in March this year, fell sharply to 6.1 per cent from seven per cent in the previous quarter, while growth for the year as a whole was also expected to decline correspondingly. India’s GDP during the past fiscal grew at 7.1 per cent — at a rate lower than the eight per cent achieved in 2015-16. In terms of gross value added, which excludes taxes but includes subsidies, the growth came in even lower at 5.6 percent over 2015-16.

“Demonetisation is a textbook example of what happens when you remove liquidity that is the basis of transactions. The immediate result was that people didn’t have money even for small transactions. This had a strong negative multiplier effect, most evident in the informal sector,” Ghosh said.

“Cash is the means of transaction in the unorganised sector, which contributes 45 per cent to the GDP. The unorganised sector got hit by 60-80 per cent,” Kumar said, adding that the country went through a negative rate of growth in November-December 2016.

In October, the International Monetary Fund said in its latest World Economic Outlook that India’s economic growth for 2017 and 2018 would be slower than earlier projections. The report cited the “lingering impact” of demonetisation and the Goods and Services Tax (GST) for the expected slowdown, projecting a growth of 6.7 per cent in 2017 and 7.4 per cent in 2018 — 0.5 and 0.3 percentage points less, respectively, than earlier projections.

Ghosh said that the steps on demonetisation, taken together, “generated a perfect recipe for slowdown in the economy. In fact the slowdown is likely to be much sharper than estimated because the quick GDP estimates are based on formal economic activity, and the adverse impact on informal activities have not really been taken into account”.

Ranen Banerjee, Partner & Leader, Public Finance and Economics, at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) feels the country was already cooling down when the note ban came in, and it would take some time to evaluate its impact on the macro economy. “About three to four quarters prior to demonetisation growth rates were already on a sliding path. It could well be that the economy was cooling down and the trend has continued. Attributing the slowdown solely on demonetisation is not possible as we do not have sufficient data points,” Banerjee told IANS.

Economist Dipankar Dasgupta, former professor of economics at the Indian Statistical Institute, said that although GDP in India is not calculated in a very comprehensive manner, the trend growth rate continued to be “pretty robust”. However, despite the claim by the government of ending corruption through demonetisation, “day-to-day bribes are still being taken through cash”, Dasgupta told IANS.

The objectives of dealing a blow to militancy and curbing fake money too seems not to have been met, as can be seen in Jammu and Kashmir, where, ironically, more incidents of militancy have been seen after demonetisation. “Logistics like shelter, passage and cash are mostly routed through over-ground workers and sympathisers of militants and those who could arrange high value notes in the previous system are doing so at present as well”, a senior intelligence officer told IANS in Srinagar on condition of anonymity.

Similarly, about fake currency, officials said the notes carried by militants from across the border were sophisticated copies and those who made them earlier could easily make fakes of the new currencies.

Perhaps there has been some beneficial fallout on the digital economy. Industry stakeholders feel that though the note-ban drive gave the necessary impetus to citizens to start adopting online payment platforms, a lot needs to be done by both the government and the industry to make it a success.

But was the country-wide upheaval worth it to make people adopt more digital transactions? No jury would need to deliberate for long on such a question.