The Supreme court Judgement allowing women of all ages entry into the ancient Sabarimala temple raises fundamental question on how far India’s secular constitution permits State to regulate age old religious faiths and beliefs. The conservative opinion is that disallowing women between ages 10 and 50 is integral to the faith of the temple and therefore beyond state intervention. What does India’s jurisprudence tell us on the delicate relationship between State, religion and the individual.

The apex court clarified the limits of religious freedom in a secular constitution. The Supreme Court of India in a significant judgement in Adi Saiva Sivachariyargal Nala Sangam & ors. Versus The Government of Tamil Nadu & Anr said, “…while the right to freedom of religion and to manage the religious affairs of any denomination is undoubtedly a fundamental right, the same is subject to public order, morality and health and further that the inclusion of such rights in the Constitution will not prevent the State from acting in an appropriate manner, in the larger public interest…”

The often quoted argument is that courts have no role in religious matters as Article 26 of the Indian Constitution provides for religious freedom.

But, the ecclesiastical jurisprudence rejects this argument. The Supreme Court repeatedly held the view that a religious institution has freedom to manage its own affairs in matters of religion. But this right guaranteed under Article 26 of the Constitution of India cannot be either absolute or arbitrary. Such freedom is confined to essential elements of a religious practice as stated by the apex court judgments in cases like Sri Venkataramana Devaru and Others Vs. State of Mysore and Others and Durgah Committee, Ajmer and another Vs. Syed Hussain Ali and others.

Justice Gajendragadkar was of the view, “……. that in order that the practices in question should be treated as a part of religion they must be regarded by the said religion as its essential and integral part; otherwise even purely secular practices which are not an essential or an integral part of religion are apt to be clothed with a religious form and may make a claim for being treated as religious practices within the meaning of Article 26. Unless such practices are found to constitute an essential and integral part of a religion, the claim for the protection under Article 26 may have to be carefully scrutinised; in other words, the protection must be confined to such religious practices as are an essential and an integral part of it and no other. ” The SC explicitly reiterated the Court’s power to decide on what constitutes an essential religious practice.

Therefore, the religious institutions, organisations or their believers cannot claim supremacy or immunity from the tenets of secular constitution of India in the name of faith and the constitutionally sanctioned freedom to pursue, propagate it. But, this is not to argue that secular institutions like courts or government can always interfere in religious affairs. The observations made in the minority view in the Supreme Court judgement in Commissioner of Police and Others Vs. Acharya Jagadishwarananda Avadhuta and Another are worth mentioning here.

The para 57 of the said view reads as follows: “The exercise of the freedom to act and practise in pursuance of religious beliefs is as much important as the freedom of believing in a religion…. there are some forms of practicing the religion by outward actions which are as much part of religion as the faith itself.

The freedom to act and practise can be subject to regulations in our Constitution, subject to public order, health and morality and to other provisions in Part III of the Constitution. However, in every case the power of regulation must be so exercised with the consciousness that the subject of regulation is the fundamental right of religion, and as not to unduly infringe the protection given by the Constitution.

Further, in the exercise of the power to regulate, the authorities cannot sit in judgement over the professed views of the adherents of the religion and to determine whether the practice is warranted by the religion or not. That is not their function.” The freedom of religion under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution is not only confined to beliefs but extends to religious practices and hardly requires reiteration. However, Right of belief and practice guaranteed by Article 25 is subject to public order, morality and health and other provisions of Part III of the Constitution.

Public order will be in jeopardy if in a diverse religious society, various religious bodies give unlimited interpretation of the religious freedom enshrined in the Constitution of India. As Pratap Bhanu Mehta points out in ‘Passion and Constraint: Courts and the Regulation of Religious Meaning’ in Rajeev Bhargava’s (ed) ‘Politics and Ethics of the Indian Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2008), in most constitutional settings , courts “have to determine whether or not a policy places a substantial burden on the free exercise of religion. ”

Public interest versus religious freedom

The wording of Articles 25 and 26 (the provisions related to religious freedom), said Marc Galanter (Law and Society in Modern India, Oxford, 1997), establishes primacy of public interest over religious claims and provides a wide scope for governmentally sponsored reforms.

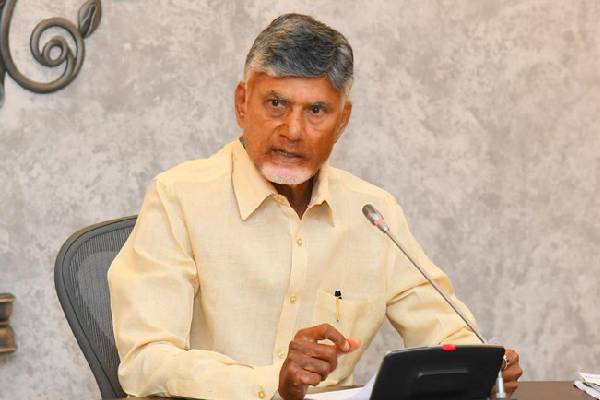

( Prof.K. Nageshwar is India’s noted political analyst. He is a former member of the Telangana Legislative Council and professor in the Department of Communication & Journalism, Osmania University, Hyderabad, India )